Although addiction counselors treat dependencies of all kinds, few have been as critical or devastating in recent years as the American opioid epidemic.

Starting in the late 1990s, the opioid crisis has overwhelmed and dominated the addiction treatment industry. In fact, in some ways, it has come to dominate the American human services sector as a whole. From social services to criminal justice, almost every field has come to revolve around both the scourge of addiction and its inevitable rippling consequences.

For many of today’s addiction counselors, life during the opioid crisis is all they have ever known. But they might not know exactly how we got here. The lessons of the past could have prevented this crisis. Understanding them now may be the key to stopping the next.

The 1800s: Opium Is an Old Adversary in American Addiction Treatment

In some ways, opioids are as American as apple pie.

In some ways, opioids are as American as apple pie.

It’s even legal to grow opium poppies in the United States, but not particularly economical, since a large, colorful crop is tough to hide, and a scarecrow isn’t enough to keep motivated thieves at bay. Also, farmers growing them for seeds or the flowers themselves generally need a DEA permit.

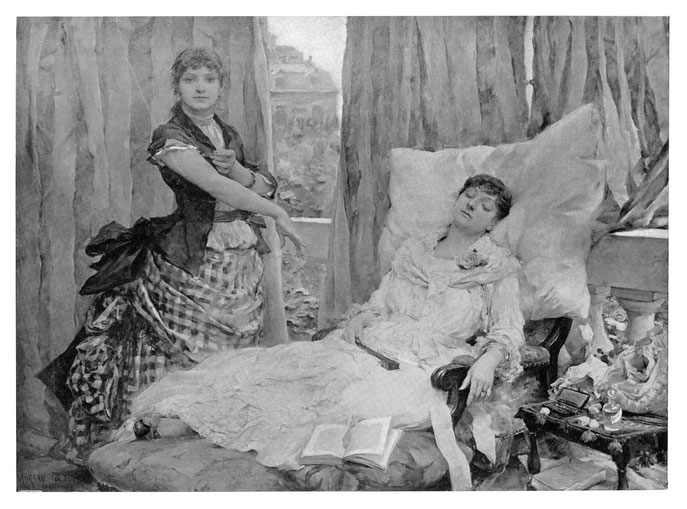

Opium largely came to American shores with early waves of Chinese immigrants in the 1800s. Opium dens, where the drug was smoked, popped up in most major American cities. A derivative of the opium poppy, morphine, was the wonder drug of the Civil War, suppressing the extreme agonies of millions of casualties on both sides… and leaving hundreds of thousands addicted after the war.

San Francisco was the first in the nation to enact an anti-drug law with an ordinance in 1875 that banned opium dens.

Heroin was first synthesized from morphine in the late 1800s and was sold over the counter in the U.S. The solubility of the derivative made it faster and more effective at penetrating the blood-brain barrier than morphine, and the potency made it even more addictive. Underground subcultures of users and smugglers emerged, leading a Special Deputy Police Commissioner in New York City to estimate in 1924 that 94 percent of criminal drug arrests were related to heroin.

A drop in commercial production and tighter border controls put heroin on the back burner in the 1930s, and the Second World War dramatically cut supplies in the U.S. Yet American consumption of opioids of all kinds has eclipsed the world.

The Next 100 Years, Though the 1990s: Prescription Pain Medications Became the Gateway to Opioid Addiction for Millions

As doctors became more aware of the risks of addiction in the early 1900s, they also cut back on prescribing opioid-based medications. That reduced the pool of people facing potential addiction, but the drug never entirely disappeared. Heroin was the opioid of choice in the United States well into the 1980s, though it was overshadowed in the larger world of addictions by amphetamines such as cocaine and meth.

As doctors became more aware of the risks of addiction in the early 1900s, they also cut back on prescribing opioid-based medications. That reduced the pool of people facing potential addiction, but the drug never entirely disappeared. Heroin was the opioid of choice in the United States well into the 1980s, though it was overshadowed in the larger world of addictions by amphetamines such as cocaine and meth.

That all changed in the mid-1990’s.

In 1995, Purdue Pharma received approval for producing OxyContin, a powerful synthetic opioid. At the same time, and partly connected with the marketing efforts behind the drug, the medical industry began loosening restrictions on prescribing such powerful medications. Pain management started to become elevated over considerations for long-term abuse, helped along by a steady stream of marketing dollars.

The Early 2000s – 2015: The First and Second Waves of the Modern Opioid Epidemic

The outcomes were predictable to anyone with a sense of the history of addictive medication. CDC (Centers for Disease Control) data showed that prescription opioid sales in the country quadrupled between 1999 and 2010. In the same timeframe, later known as the First Wave of the current opioid crisis, overdose deaths doubled.

The outcomes were predictable to anyone with a sense of the history of addictive medication. CDC (Centers for Disease Control) data showed that prescription opioid sales in the country quadrupled between 1999 and 2010. In the same timeframe, later known as the First Wave of the current opioid crisis, overdose deaths doubled.

Shifts in the heroin production and smuggling market at the same time dumped gasoline on the first. While South America had been the major source of the drug for some decades, increasing production in Mexico made the supply more accessible and street prices less expensive. Anyone who got a taste for that opioid high from prescription meds suddenly had an easy way to keep the lift going with heroin.

In 2010, overdose deaths from heroin started to rise in a Second Wave as well. By 2015, it had overtaken the lead from prescription opioids.

But the ride wasn’t over, by a long shot.

2016 – Today: In the Third Wave, Fentanyl Comes on the Scene and Every Fix Becomes a Dice Game With Death

New advances in synthetic opioid production in the early 2000s put a newer, cheaper, even more dangerous drug on the streets: fentanyl.

New advances in synthetic opioid production in the early 2000s put a newer, cheaper, even more dangerous drug on the streets: fentanyl.

Extremely potent, easy to make, and less expensive all the way around, “fetty” is a drug dealer’s dream. In the beginning, it was simply used to boost the potency of street heroin, cutting costs. But creative marketing saw it being pressed into fake replicas of real prescription opioids, laced into other drugs like cocaine, or even used directly.

This explosion of availability combined with the potency drastically increased the opioid death rate once again. Between 2015 and 2020, the rate doubled again in the Third Wave of the current opioid crisis.

An Escalating Public Health Emergency Demands New Treatment Professionals

In 2017, the Department of Health and Human Services declared the opioid crisis to be a public health emergency. It’s easy to see why.

The Third Wave, seen on the charts, looks like a sheer vertical wall compared to the soft swells of the initial waves. The death rate more than doubled. And that was despite a serious effort pushing fast-acting antagonists like naloxone out into the public, with first-responders preventing many potentially fatal overdoses.

All told, between 1999 and 2022, nearly 727,000 died from opioid overdose. Even that is only a fraction of the lives that substance abuse counselors have watched fall into ruin as a result of addiction during that period, though.

One study found that the opioid epidemic accounts for more than half of the decline in men’s labor force participation rates between 1999 and 2015.

Data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health shows around 1.5 million illicit opioid users per year, and each of them drags a tragedy of pain and sorrow through families and communities. Other studies have shown that the second and third waves of the epidemic decreased employment, increased the burden on Social Security Disability Insurance, and increased levels of incarceration in the country.

Is a Fourth Wave Eminent, or Is the Opioid Crisis Ready To Fade Into the History Books?

Will there be a Fourth Wave in the opioid crisis? It’s too soon to say. But there are reasons that addiction counselors are feeling optimistic lately.

Starting in 2016, the overall consumption of prescription opioids had been dropping for five years in a row. That minor glimpse of success was eclipsed by increasing overdose deaths from illicit drugs. But the decreased use still indicates that many people managed to side-step the danger and tragedy that the previous generation walked directly into. This should continue to pay dividends going forward.

Some of the fruits of those efforts are already showing up. In 2025, the CDC announced that there had been an incredible decrease of almost 27 percent in overdose deaths in 2024 compared to 2023. That’s the lowest rate since 2019, although 2019 itself was a fairly terrible year. But at least the number is finally moving in the right direction.

Why Addiction Counselors Are Becoming Optimistic About Outcomes in the Opioid Crisis

Some of this is cyclical, a part of the supply and demand and the unfortunate reality that so many buyers have died. But much of it is down to the hard work of addiction counselors and prevention specialists hard at work at every level of public health.

Congress has put more than $10 billion toward the opioid crisis since 2017, and another $50 billion in funding has trickled down to states and local governments through settlements with various drug manufacturers and distributors.

That money goes into prevention and treatment programs, part of it fueling treatment for around 370,000 people each year – about a quarter of those currently using opioids. Unfortunately, that number has actually dropped, as well, down from some 670,000 in treatment in 2018.

One of the bottlenecks to serving more of that population is a shortage of trained and qualified addiction counselors.

The Impact of the Opioid Crisis on Addiction Counselor Education

That shortage of counselors has spurred significant changes in the licensure of substance abuse treatment professionals.

That shortage of counselors has spurred significant changes in the licensure of substance abuse treatment professionals.

Some of these changes have been easy and practical… it’s an unusual counselor who works with this population today who doesn’t carry Narcan, for instance. That small, practical step has likely saved thousands.

Other shifts have been broader. A new emphasis on research and evidence-based treatments is woven into the pipeline. More states have passed regulations regarding credentialing and education that have improved training and professionalized the workforce.

At the same time, the need for boots on the ground has also expanded credentialing downward. A 2003 survey of counselors in the Pacific Northwest found that almost three-quarters held bachelor’s degrees or higher. By 2016, an HHS survey found that percentage nationwide had dropped to a little over half. Moreover, it found that community colleges were the source of most specialized SUD counseling training, and that certification in addiction treatment was more common for counselors with lower degree levels.

This demand for counselors quickly has shown that critical education can happen even through quick certificate programs or associate degrees in addiction counseling.

The Opioid Epidemic Has Helped Integrate Addiction Counseling With Other Behavioral and Physical Healthcare Services

Many of the most important changes haven’t actually been in addiction counselor training and education, but instead in the health sciences field. Reacting to the role of overprescribing opioids in fueling the crisis, there’s a new emphasis on pain management, SUD diagnosis, and integration with professional addiction counselors in doctor and nursing education.

This emphasis on interprofessional cooperation is an equally important shift on the counseling end of the educational spectrum, too. Where addiction therapy was once taught as a more independent activity, it’s now being shown as a critical part of a larger interdisciplinary care team for most patients.

That expands treatment options and gives addiction counselors new capabilities through coursework in pharmacology, co-occurring disorders, and treating diverse populations… all now standard, and relatively recent additions to the core SUD treatment curriculum.

The history of the opioid epidemic in the United States is still being written. Counselors graduating today will hopefully close the book on it and build a happier future for the country.